Why We Don’t Let the Flag Touch the Ground?

My last Flag-Post.com article considered the rule in the U.S. Flag Code, “The flag should never touch anything beneath it, such as the ground, the floor, water, or merchandise.” At the end of that article, I promised to explain how this rule came to be. While the historical record does not fully explain everything, we can get a good idea of how this came to be by studying our nation’s history.

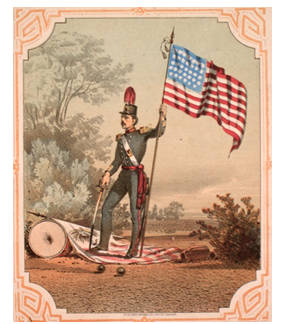

Many of the rules and traditions governing display of the Stars and Stripes grew from the national experiences of the U.S. Civil War. Before that conflict, the flag was used mainly by the government and the military. Private individuals and businesses seldom flew the U.S. flag, and the strong feeling of love and respect for the flag did not exist as we know them today.

“Down with the Traitor’s Serpent Flag”, Flint & Higgins, 1861.

During the war, many cartoons and illustrations published in newspapers and magazines, showed “enemy” flags thrown to the ground while triumphant soldiers held their flags high in defiance. At an 1862 Christmas wedding celebration in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, “giddy Confederates danced on floors carpeted with the American flag.” During the Battle of Murfreesboro a few days later, Union flag bearer William H. Steel of the 34th Illinois Infantry Regiment was shot seven times while carrying the Stars and Stripes into that battle.

Carrying the flag into battle during the Civil war was a great honor, but also extremely dangerous as flag bearers were good targets. Flag bearers on both sides of the conflict were almost always killed or wounded while carrying their flags into battle. During only one day of battle in Gettysburg, twenty-three color bearers from two units were killed during the fighting. As one man was shot, another would grab the flag and would in turn be shot.

Perhaps the most dramatic incident of a wounded flag bearer is the story of Sergeant William H. Carney of the famed 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry Regiment chronicled in the movie “Glory.” Sergeant Carney was severely wounded during the attack on Fort Wagner. The 54th was driven back but Carney, although wounded continued to carry the flag. As the regiment withdrew, a member of the also retreating 100th New York Infantry Regiment, seeing Carney’s wounds offered to carry the flag for him. Carney refused saying, “No one but a member of the 54th should carry the colors.” Struggling back to the Union lines, Carney was wounded again, but continued to carry the national color. When Carney finally carried the flag to safety behind Union lines, he collapsed as other members of the 54th grabbed the flag. Carney’s words as he at last handed off the flag were, “Boys, I only did my duty. The flag never touched the ground.” For his heroism Carney was the first African American to receive the Medal of Honor.

From these and many other stories, it is easy to see how a flag touching the ground came to be viewed as an insult and how it came that we honor the flag by not allowing it to touch the ground. Logically it makes sense, but emotionally it expresses love and respect rooted in the Civil War that has grown over the years to become unquestioned by those who choose to honor the flag.

The painting The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground, which depicts the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment at the attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863.

Abraham Lincoln also attached strong symbolic meaning to the Stars and Stripes, and while many suggested changes reflecting Southern secession, Lincoln refused. In my next blog I will tell the story of one unusual change to the U.S. flag suggested by Samuel F.B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, who sought desperately to avoid the coming conflict.

This makes a lot of sense, could another reason be the sacrifice made at Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. When the people of Fort McHenry refused to let the flag fall and piled their bodies all around the flag pole to keep it standing through the night.

Maybe the reason we do not let the Stars and Stripes fall is because it would dishonor all those who kept it standing throughout all the conflicts, that thei4 sacrifice will not be in vain.