The Story of Martyrs and a Confederate Flag

A few flags have stories that make them famous. Although it is largely unknown today, one Confederate flag gained wide fame in the North and in the South during early days of the Civil War. The story of this one flag is tied to the fate of the first two martyrs of the war: Elmer E. Ellsworth and James W. Jackson.

Elmer Ellsworth, like Abraham Lincoln, grew up the son of poor parents. Although he had no formal military education, he studied military science in his spare time and became the drillmaster of militia groups. Only five and a half feet tall, Ellsworth studied law in Lincoln’s law office, campaigned to elect Lincoln, and became Lincoln’s close friend. Considering Ellsworth almost as a brother, Lincoln is said to have called him “the greatest little man I ever met.”

James W. Jackson, the innkeeper of the Marshall House Inn was a passionate secessionist known for his violent temper. The Marshall House was found on the Virginia side of the Potomac River across from the city of Washington. Jackson, who raised the Confederate flag known as the Stars and Bars over his hotel on the 17th of April in 1861 soon after the fall of Fort Sumter, vowed that only “over [his] dead body” would the flag be removed.

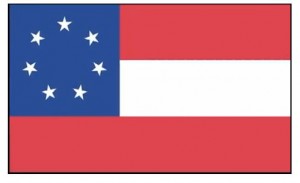

Confederate flag as it appeared when first raised over the Marshall House Inn had seven stars in its union symbolizing the first seven states of the Confederacy.

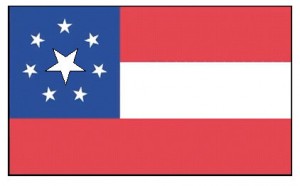

When the new President moved to the nation’s capitol, Ellsworth accompanied the family. However, after the fall of Fort Sumter he travelled to New York where he helped enlist the 11 New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and he returned to Washington with the regiment and as its commander. Colonel Ellsworth, using a telescope, spotted a large Confederate flag flying over a building in neighboring Alexandria, Virginia. James W. Marshall, the innkeeper of Alexandria’s Marshall House, had obtained a large Stars and Bars flag measuring 14 feet by 24 feet which he raised on a 40 foot flagpole over his hotel. Instead of thirteen stripes, the flag had three wider bars of red, white and red. In the blue canton, where 33 stars were found on the U.S. flag, this flag had seven stars in a circle representing the first seven states to join the Confederacy. Ellsworth with the aid of a telescope could see the flag from the White House’s second story window and he found the “secessionist rag” flying over the Marshall House. Finding the display an offense to President Lincoln, Ellsworth wanted to remove the flag, but Virginia had not yet seceded, and Ellsworth had no authority to do anything about the flag. Things changed on May 23 as Virginia seceded and a large star was added in the center of the Marshall House flag’s union to signify that Alexandria, along with the rest of Virginia, was in open rebellion against Federal authority.

With Colonel Ellsworth and the New York 11th Regiment part of its force, the Union Army crossed the Potomac River to capture Alexandria, and the New York 11th under Col. Ellsworth’s command received the assignment to capture the railroad station and the telegraph office. Entering the city uncontested, the soldiers of the 11th marched down the street directly past the Marshall House Inn with its huge flag flying over the building. Colonel Ellsworth rode past the hotel, but stopped and looked back at the huge flag. Apparently, his assigned mission did not seem as important to him as removing the offensive flag from the Marshall House’s flagpole. No doubt he was anxious to present the flag to President Lincoln. So, rather than leading his men to their assigned objectives, Colonel Ellsworth sent men on ahead to capture the train station and telegraph office while he turned his attention to a hotel and its flag.

The Confederate flag flown over the Marshall House Inn, when Union troops entered Alexandria, had an additional large star for the state of Virginia which had just seceded.

Sound military procedure would dictate that he should have sent a patrol to first secure and clear the building. Then he could send a detachment up to the roof to cut down the flag, and it could easily have then been dropped to the ground for Ellsworth to collect. However, the colonel was intent on retrieving the flag with his own hand.

Ellsworth took three men with him as he entered the hotel: the Regimental Chaplain, a staff officer who had been a newspaper man before joining the Army, and a civilian reporter from the New York Times. He also ordered a couple of corporals to follow his flag detail.

Upon entering the hotel, a half awake and half dressed man met them in the hall. Ellsworth demand to know why a Confederate flag was flying over the building. The man answered that he was just a hotel guest and didn’t know anything about the flag, and Ellsworth let the man go as he charged up the stairs to the top floor. The man was in fact James W. Jackson, the Marshall House Inn’s proprietor, who disappeared into a back room without being kept under any surveillance.

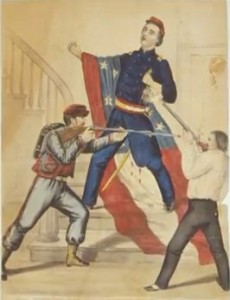

Ellsworth’s party found a ladder on the top floor which led to the roof, and they climbed out on the roof where, with some difficulty, they cut down the flag and stuffed it trough the trap door. It was not easy for the three men to climb down the stairs as they carried the enormous flag. In the meantime, the unsupervised Jackson appeared on the landing carrying a shotgun which he aimed point blank at Ellsworth and fired. One of the corporals fired his rifle at Jackson hitting him in the face and then thrusting his bayonet into the hotel innkeeper’s body. Both Ellsworth and Jackson died on the spot, and the Marshall House flag became the symbol of the double martyrdom.

The innkeeper, James W. Jackson, shoots Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth as Corporal Brownell in turn prepares to shoot his commander’s killer.

Newspaper accounts, dramatic pictures, poetry, sheet music and songs glorified Ellsworth in the North as the first martyr to the Union cause. Members of the 11 New York Regiment cut souvenir pieces from the flag until only about sixty percent of the material remained. The remaining portions of the flag finally came into the possession of the New York Military Museum where the flag was recently cleaned and conserved.

In the South James W. Jackson was acclaimed as the Alexander Hero, the Slayer of Ellsworth, the First Martyr in the Cause of Southern Independence. The Marshall House Inn was torn down in the mid twentieth century to make room for a modern hotel, and only a historical marker remains at the site to commemorate Jackson with the words, “The justice of history does not permit his name to be forgotten.” Nevertheless, the marker fails to mention the killing of Ellsworth.

A group of vexillologists (flag historians) visit the site of the Marshall House Inn with a replica of the Confederate flag Colonel Ellsworth cut down in 1861.

Today Ellsworth, Jackson, the Marshall House Inn and the flag are remembered only by Civil War buffs and vexillologists (flag historians). Fame in this case came quickly but faded with the years.

My next postings will tell more stories of Lincoln and Civil War flags.