Stars in Their Eyes

Thirteen Star U.S. Flag commonly called the Betsy Ross Flag.

The oft told story of Betsy Ross relates that George Washington, Robert Morris and George Ross visited her shop announcing themselves as a delegation on an errand from Congress. Mrs. Ross, a young widow, received an order from the three men to sew a flag made up of thirteen red and white stripes completed with a blue union in the upper corner containing thirteen white stars. Washington, of course, was the commanding General of the Continental Army. Morris, a wealthy man, was a leading member of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and George Ross was the uncle of Betsy’s late husband and an influential Colonial leader in the cause for American Independence.

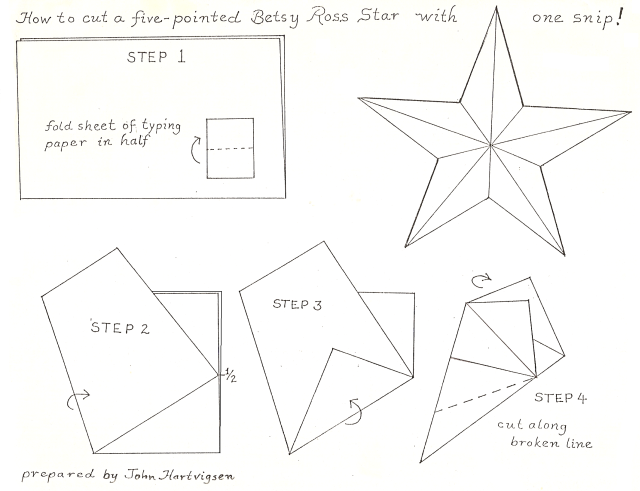

The delegation produced a drawing of the flag showing the thirteen stars each with six points. Mrs. Ross suggested that a five pointed star would be better. The men, while agreeing, felt that a five pointed star would be more difficult to make. The young widow made a few quick folds on a piece of paper and with one snip of her scissors produced a perfect five pointed star. The men left her to her task and, according to the narrative, Betsy Ross made the first stars and stripes. A seemingly simple story, but there are many versions that add many details; however, our story is about the stars.

Many of the myriad of details recorded in the numerous versions of the Betsy Ross story had been attacked by critic as false. To be certain many details do run counter to accepted history; nevertheless it is the story of cutting a five pointed star which attracts some of the most scathing criticism.

Milo M. Quaife, a noted historian, argued “…the naïve conception, inherent in the entire story, that at a time when the life of the nation was hanging in the balance, men of the intellectual caliber and heavy responsibility of George Washington and Robert Morris would fritter away an afternoon in familiar discussion with an indigent seamstress over the trifling detail of how the stars in a flag should be cut and arranged exceeds the reasonable bounds of human credulity.”

Yet, there are other details which could support the story. Washington’s staff had without success repeatedly requested battle flags from Congress. Admittedly these were military flags or colors and not a flag for a new nation. Nevertheless, one type of flag desired by Washington was what we would now call a National Color, a flag to represent the combined Colonies. In early June of 1776 Washington did in fact visit the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. This was soon after the Siege of Boston where Washington outfoxed the British commanders and the Continental Army forced the British troops to board ships and evacuate Boston. It is not unreasonable to contend that, tired of Congresses’ inaction concerning his requests for flags, the Commander in Chief took Robert Morris in town and visited someone to make a flag as an example. Not a national flag, since adoption of the Declaration of Independence was still weeks in the future, but an example of what could be used as a flag or color that would represent the united colonies.

Quaife’s assertion that Washington would not waste his time talking to a woman, seems condescending and chauvinistic. Washington, who was known to take interest in minute details, had even designed his own uniform and concerned himself with rank insignia. If he wanted to know about flags, it is reasonable that he would visit a seamstress. If only in Philadelphia for a few short days, he would likely not delay by sending someone else.

Why would Betsy Ross bother her visitors about the number of points on a star? As Professor Marla Miller commented in her exhaustive volume Betsy Ross and the Making of America, Betsy Ross was not a designer, but a fabricator. Anyone who has made a U.S. flag with appliquéd stars knows that making the stars, cutting them out and sewing them in place is tedious and time consuming. Thirteen stripes are easy, but for a double appliquéd 13 star flag twenty-six stars are needed. While there are tricks modern flag makers use, Betsy Ross’ contemplation of cutting out thirteen six pointed stars would influence her to suggest anything that would shorten the task. If she knew a quilters trick to produce a five pointed star quickly, she would have understandably argued for that option. For the men, that may have not been an important detail. However, the details of how a star on a U.S. flag is made, is important today. Try making a flag with six points now, and complaints would multiply.

Grab a 9″ by 11″ inch sheet of paper and a pair of scissors. A few folds and one snip and you can create a perfect five pointed star.

A folded piece of paper labeled “Betsy Ross Pattern for Stars–“ was found in an old locked safe that blown open in 1922 to reveal its contents. Owned by the Wetherills, a Free Quaker family including Betsy Ross’ business associates, the safe had been locked for many decades when it was finally opened. The folded paper is, to supporters of the Betsy Ross Legend, an artifact supporting the story. Does the pattern prove that Betsy Ross sewed the fist Stars and Stripes? No, but it does show how easily Betsy could have cut a star using one snip of her scissors.

Did Betsy Ross actually sew the first Stars and Stripes? Contemporary evidence does not support the story. On the other hand, nothing has been found to prove that someone else deserves the credit. Dr. Marla Miller suggests that there may be some truth in the central claim. It may be written in the stars.

At Colonial Flag, we can create custom flags (even Betsy Ross’s, if you desire) following your design.