Lincoln Refused to Remove Stars from the U.S. Flag

Lincoln raising the 34 star flag in Philadelphia on Washington’s Birthday in 1861.

With Lincoln’s election to the U.S. Presidency, state legislatures in the slaveholding south met to declare their secession from the American Union. In the Nation’s Capital, Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis rose in the U.S. Senate chamber on January 10, 1861 for the last time before resigning his office after which he assumed the Presidency of the Confederate States of America. Davis likely echoed the feeling of Southerners when he mused that the Stars and Stripes would “. . . no longer be the common flag of the country.” He went on to recommend that the flag “. . . be folded up and laid away like a vesture no longer used; that it shall be kept as a sacred memento of the past . . . .”

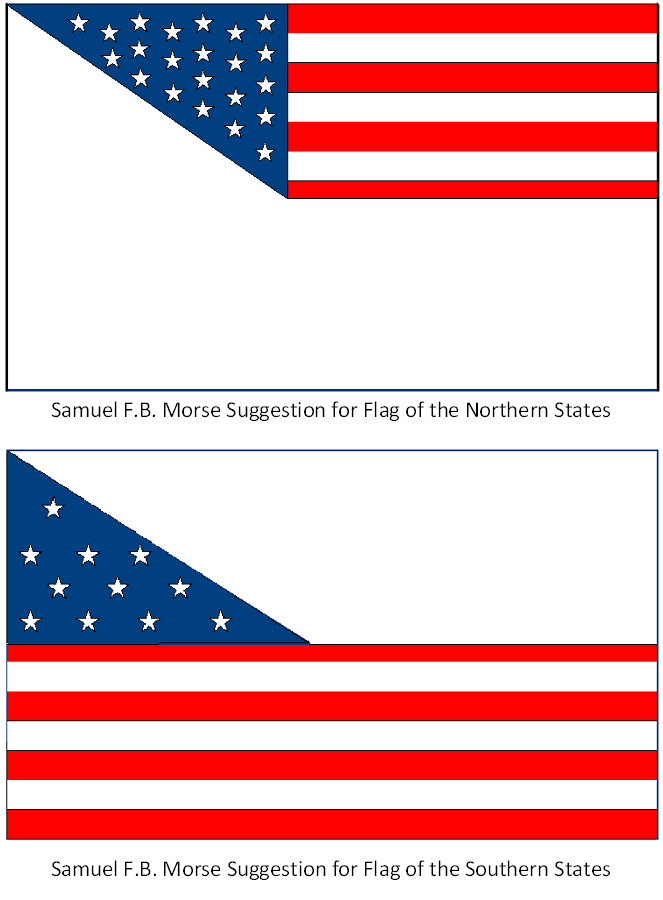

Although a Northerner, Samuel F. B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, desperately urged the federal government to avoid armed conflict with the seceding southern states. Rather than following Jefferson Davis’ suggestion that the U.S. flag be retired, Morse suggested that the flag be divided just as the map of the nation was cut in twain by the loss of the Confederate States. Morse designed flags that gave each group of states six and one half stripes, and the union would also be divided diagonally giving the North a blue triangle with 22 stars and the South a triangle with 11 stars. Each flag would be completed with white where lost stars and stripes had once been. Morse hoped for a peaceful parting that would allow a happy reunion of states at some future date when differences would be overcome; nevertheless, his hope for a peaceful separation and the adoption of two peace flags failed to gain support.

Although a Northerner, Samuel F. B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, desperately urged the federal government to avoid armed conflict with the seceding southern states. Rather than following Jefferson Davis’ suggestion that the U.S. flag be retired, Morse suggested that the flag be divided just as the map of the nation was cut in twain by the loss of the Confederate States. Morse designed flags that gave each group of states six and one half stripes, and the union would also be divided diagonally giving the North a blue triangle with 22 stars and the South a triangle with 11 stars. Each flag would be completed with white where lost stars and stripes had once been. Morse hoped for a peaceful parting that would allow a happy reunion of states at some future date when differences would be overcome; nevertheless, his hope for a peaceful separation and the adoption of two peace flags failed to gain support.

One man in East Fairhaven, Massachusetts raised a flag patterned after Morse’s odd suggestion for the flag of the southern states. Not only did his neighbors disapprove and force the flag to be lowered, a mob tarred and feathered the man and forced him to promise to never fly any flag but the full complement of Stars and Stripes.

As the Presidential Inauguration in 1861 was still held on the 4th of March, Lincoln did not leave his home in Springfield until the 11th day of February, and with his journey through sixteen cities he would not arrive in Washington until the 23rd of February. Even before the new President could take the oath of office, southern states—led by South Carolina on December 20th of 1860—declared their intent to secede from the Federal Union and by the time Lincoln reached Philadelphia on February 22nd, Washington’s Birthday, five states had seceded. Lincoln did not pay attention to the seceding states; rather he took special notice of Kansas which was being admitted to the Union as others declared their intentions to leave.

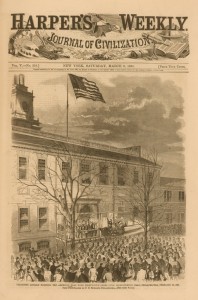

Harper’s Weekly cover for March 9th of 1861 highlighted Lincoln raising the 34 star flag at Independence Hall.

Kansas joined the Union on the 29th of January as the thirty-fourth state; nevertheless, the new star for the state would not officially appear in the starry union of the United States flag until the following Independence Day, July Fourth of 1861. This notwithstanding, a new thirty-four star flag was hurriedly sewn up for the President Elect to raise at Independence Hall on George Washington’s Birthday. On this significant occasion Lincoln did not merely watch as others raised the new flag, but rather with his own hands he raised the flag to the top of the flagstaff. Lincoln told the assembled crowd that while the original stars and stripes raised at Independence Hall had only thirteen stars, “I wish to call your attention to the fact, that, under the blessing of God, each additional star added to that flag has given additional prosperity and happiness to this country . . . .” He continued “I think we may promise ourselves that . . . the new star placed upon that flag [the star for Kansas] shall be permitted to remain there to our permanent prosperity. . . .” He made no mention of removing any stars from the flag, but only of continuing to add additional star and states. Throughout the Civil War Lincoln refused any attempt to remove any stars from the flag of the Union as he reasoned that states had no constitutional right to secede, and they were all therefore still in the Union.

There were three versions of the Stars and Stripes in use during the Civil War, but each added a new star for a new state. My next blog article will tell more of the story of Abraham Lincoln, Old Glory and the Civil War.